In May 2021 I started posting educational geoscience videos on TikTok to test the waters of short-form video for science communication. I quickly found enjoyment both in creating and consuming content on TikTok, and I have continued to use TikTok as my primary platform for science communication.

In our research study published in November 2022, we demonstrated that TikTok is an extremely promising platform for geoscience communication, providing significant potential for the reach and growth of science communication content. As TikTok has continued to rise in popularity, other social media platforms have attempted to mimic the success of short-form video seen on TikTok—namely Shorts on YouTube and Reels on Instagram and Facebook.

As other platforms have prioritized short-form video more and more, many creators (and science communicators) have been cross-posting their TikTok videos to other platforms. Cross-posting the same content to different platforms can help find new audiences and highlight the nuances and algorithmic differences in platforms.

I decided to expand my short-form geoscience content to YouTube starting in October 2022 and re-uploaded a number of my TikTok videos as YouTube Shorts. I was curious to see if YouTube could provide the same impressive reach that TikTok does for science communication content, but unfortunately YouTube Shorts falls short in my eyes.

TikTok vs YouTube Shorts basics

Although TikTok videos were originally restricted to under 60 seconds long, TikTok has increased the in-app recording duration to 3 minutes long and allows pre-filmed videos up to 10 minutes long. TikTok has two primary feeds to watch videos: the For You feed and the Following feed. The For You page is a feed of algorithmically recommended videos tailored to the user, and the vast majority (~75%) of content on TikTok is consumed via the For You page.

Since YouTube Shorts joins the existing long-form videos on YouTube, all Shorts videos must be under 60 seconds long. Any video uploaded to YouTube under 60 seconds will automatically be classified as a Short. Short videos can be viewed within the specific Shorts feed on YouTube, but they can also be found and viewed in all the same manners as long-form content (via subscriptions, on home page, via search, as recommended content).

The 60 second limit on YouTube Shorts videos poses restrictions on the length of TikTok videos that can be re-uploaded to the platform. If your video is 90 seconds long, it will be a “regular” video on YouTube and is not classified as a Short (and thus will not show up in the Shorts feed).

On TikTok, you can customize the thumbnail of the video by selecting a frame of the video and adding text, while you currently cannot customize or choose the thumbnail of the video on YouTube Shorts. (Much to my ire, this has resulted in some extremely unflattering video screenshots chosen as the YouTube Shorts thumbnail that I have no way to customize or change. I really hope this is something that will soon change in the future.)

TikTok brings the views

I re-uploaded 30 of my TikTok videos to YouTube as YouTube Shorts so I could compare how the same exact content performed on the two platforms. Both of these accounts started at zero followers, and the video titles/descriptions were kept essentially the same, as well as the hashtags used. I removed the original TikTok watermark from the re-uploaded videos so there was no branding on it.

Of the 30 videos I cross-posted, 29 of the videos received more views on TikTok than they did on YouTube. (The sole Shorts video that received more views than TikTok discussed ‘fossil’ ripple marks and had 670 more views than the TikTok—not a large margin of improvement.)

These 30 videos cumulatively received 414,200 views on TikTok, but only 24,500 views on YouTube. The TikToks had a median of 2,800 views, while the Shorts had a median of 320 views. On average, the videos on TikTok received 8 times as many views as they did on YouTube.

Interestingly, the Shorts video that received the highest number of views (8,360 views, about river meanders) received only 1.9% of its views from the Shorts feed, the designated way to view Shorts on YouTube. 96.8% of its views came from it being recommended in YouTube search results. I would have thought that if a video is being viewed heavily through other traffic sources, it would renew it being shown in the Shorts feed, but apparently not.

Screenshot of YouTube Short that received the most views, with a chart showing how viewers found the video, 96.8% from YouTube search and only 1.9% from the Shorts feed.

Viewer demographics

Knowing who your viewers are is an important factor if you are a science communicator trying to reach certain audiences. As I was growing my TikTok account, I had a disproportionate increase in the number of male followers. (The majority (54%) of TikTok users are female. ) In October 2021, it got to the point where 75% of my followers were male and only 25% were female—a very large mismatch from the demographics of TikTok users, which made it feel like science content was preferentially being shown to male users.

I made a TikTok video specifically addressing this issue, how I found it troubling, and how I’d like to be reaching more women and young girls with my content, as it is crucial to help interest and retain more women in the male-dominated STEM fields. I gained tens of thousands of followers from this video, nearly all female. To date, 83% of my TikTok followers are female and 17% are male. However, most TikTok video views do not come from followers, and an average video of mine receives 60% of its views from female users and 40% from male users. So TikTok is by no means perfect in terms of gender parity, but there are ways to correct and reach desired audiences.

With YouTube Shorts, the gender disparity of my video viewers appears even worse. Of all the viewers of my Shorts, 83% are male and less than 17% are female. (Within the US, 51% of all YouTube users are female.) What could explain this dominance of male viewers other than male users being shown science content in the Shorts feed more than female users? Why is my educational geoscience content algorithmically categorized as something for men? What do I do to fix this?

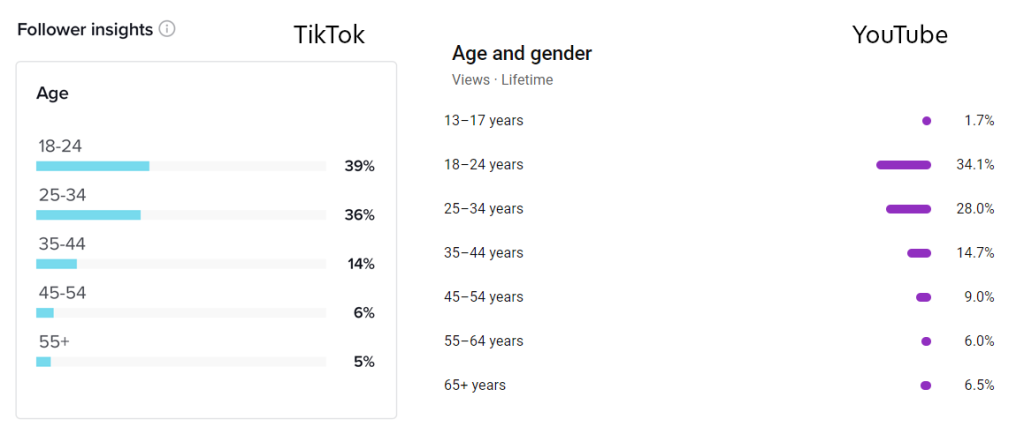

Interestingly (but perhaps not surprisingly) the age of my followers and viewers on both platforms shows about the same distribution. Most followers are between 18-24 or 25-34 years old. There are indeed users of all ages on both apps, but both user bases are equally ‘young,’ which can be critical in targeting viewers at ages where they may lose interest in STEM. Before, I would have guessed that YouTube Shorts had a slightly older audience (say people who don’t want to download TikTok), but it’s largely the same audience age-wise.

How does YouTube Shorts work?

As we confirmed in our research study, TikTok video views primarily come from videos being shown on the algorithmic For You page, which is tailored to the interests of each user, while still showing diverse content recommendations. A longer watch time and higher engagement rate are likely needed for videos to achieve high reach. TikTok accounts do not need to have a large number of followers or a large video catalog to have videos go ‘viral’ and achieve high reach.

So what is different about YouTube Shorts that result in drastically different performance of the same videos? From personal experience making long-form content on YouTube, YouTube very rarely pushes videos or promotes accounts that have very few followers (it took an incredibly long time for me to gain a following on YouTube). YouTube also appears to like it when accounts post consistently and frequently and maintain a high watch time. Do these factors weigh into the performance of Shorts that hinder the reach from new accounts? How tailored is the content shown within the Shorts feed? (I only have questions, not answers here.)

I’ve also been extremely perplexed by the timespan in which my YouTube Shorts receive views. Every Short accumulated views during a one-hour period only (not necessarily immediately after uploading). After that one-hour window passed, the views were turned off like a faucet. Even when it felt like there was this increasing momentum in views, the ‘time on the clock’ ran out and it just completely stopped getting shown in the Shorts feed. TikTok doesn’t have equivalent real-time data to compare to, but I never felt like TikTok uploads had such a short-life span.

Monetization

While many science communicators often take personal time to share science and create content without pay, monetization is an important consideration for many internet creators. Platforms that provide monetization options for creators tend to have more success in the long run, as creators will leave apps for others if adequate monetization isn’t provided.

TikTok allows creators to earn money from their videos and join the Creator Fund if they have at least 10,000 followers and at least 100,000 video views in the last 30 days.

I met the criteria to join the TikTok Creator Fund in November 2021. Since then, I have earned $15.41 from the Creator Fund. (This comes from receiving 610,000 total video views from 28 videos since November 2021.) While it’s certainly better than nothing, you would need to receive millions and millions of views monthly to gain any meaningful earnings from the TikTok Creator Fund.

YouTube debuted a new monetization program for Shorts in February 2023. To monetize your channel, YouTube requires 1,000 subscribers and 10 million Shorts views in the last 90 days (or 4,000 watch hours in the last year).

While the 1,000 subscribers requirement is very reasonable, I know I’ll never be able to monetize my Shorts videos from the unbelievably high requirement of 10 million views in 90 days. I’m lucky to get 10,000 views in 90 days from YouTube Shorts. You would either have to upload an incredible amount of videos and/or have huge success in having multiple of them going viral. All within a month and a half.

Shorts and TikToks both can easily receive tens of millions of views, but are those videos going crazy viral educational and informative like science communication content, or are they the standard kind of ‘viral’ clips that gave YouTube its start?

Final thoughts

For a few months I gave up on re-uploading videos to YouTube since I was not seeing any of the success that TikTok had provided, but I wanted to renew the effort when there were increased discussions of banning TikTok. Could I still reach an audience if TikTok goes away?

Unfortunately, YouTube Shorts still falls short to me. I’m curious if I continue to upload to YouTube more consistently and more frequently (thus hopefully gaining more subscribers), will my Shorts receive more views from within the Shorts feed? It’s certainly minimal effort to upload a video once it’s already filmed (I now film and edit my TikTok videos exclusively outside the app), but it’s disheartening to feel like Shorts is missing all the great parts of TikTok.

This discussion has also only focused on YouTube Shorts as an alternative, when Instagram Reels is the other large TikTok copy-cat/competitor. While I have not re-uploaded my personal geology TikToks to Instagram, I have cross-posted many of the TikToks created on our company account as Reels. Thus far, no cross-posted Instagram Reel has received more than 10,000 views (when the same videos on TikTok have received hundreds of thousands of views). With a few exceptions, Reels always receive equal or less views than the TikTok upload—views on Instagram feel more strongly correlated to number of followers.

I think the biggest flaw with Reels and Shorts is that they are part of existing platforms that already have tons of other content that is consumed in different ways. You may go to Instagram to view a friend’s story, and then maybe you watch a Reel if it come up. You go to YouTube to watch a 20 minute movie review, and then maybe you also watch some Shorts. Whereas you go on TikTok to watch TikToks.

TikTok has communities for every niche interest imaginable, and science content is a huge part of that. TikTok even recently announced that they were going to offer a new STEM feed to highlight the thriving science education-based communities on TikTok. Short-form video content is the new it thing for social media, and science communicators must adapt to new trends to reach audiences online. As of now, TikTok offers unparalleled reach, but I hope other platforms mature and soon follow suit.